AnimSchool instructor Daria Jerjomina has rigged characters all over the industry. In this short lecture, she not only walks through what it means to rig a character, but also discusses how it differs in each part of the industry.

Most are familiar with two stages within the 3D pipeline: modeling and animating; rigging occurs between these two steps. Rigging consists of adding a skeletal structure to the model which allows the model to respond fluidly to the animator’s directions. Without rigging, 3D animation as we know it would not exist.

Daria begins by providing a general definition of rigging: a process of setting up a character, providing an animator with a control over its movement. It falls between rigging and animation within the pipeline.

- Parts of a pipeline (not all pipelines are the exact same, but most will follow this general order):

- Visual development (concept art, storyboarding, color script, etc.)

- Modeling

- Rigging

- Animation

- Texturing

- Lighting

Riggers will work closely with both the modeling and animation departments. Animators may request specific features and functionality on the rig, and riggers may need to work with modelers to get the model best suited for adding in those features.

Rigging in Different Productions

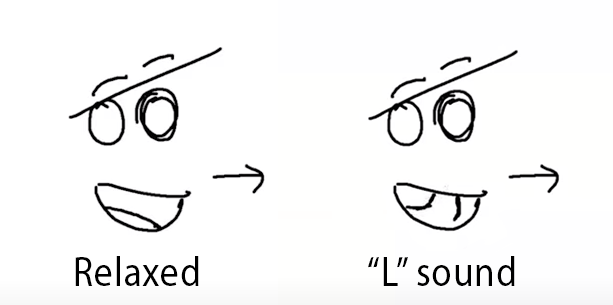

CG Feature Animation

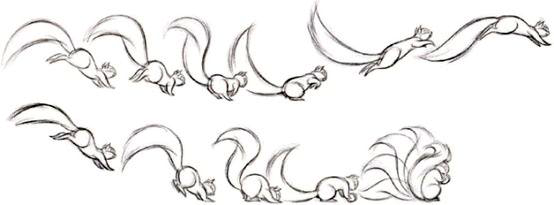

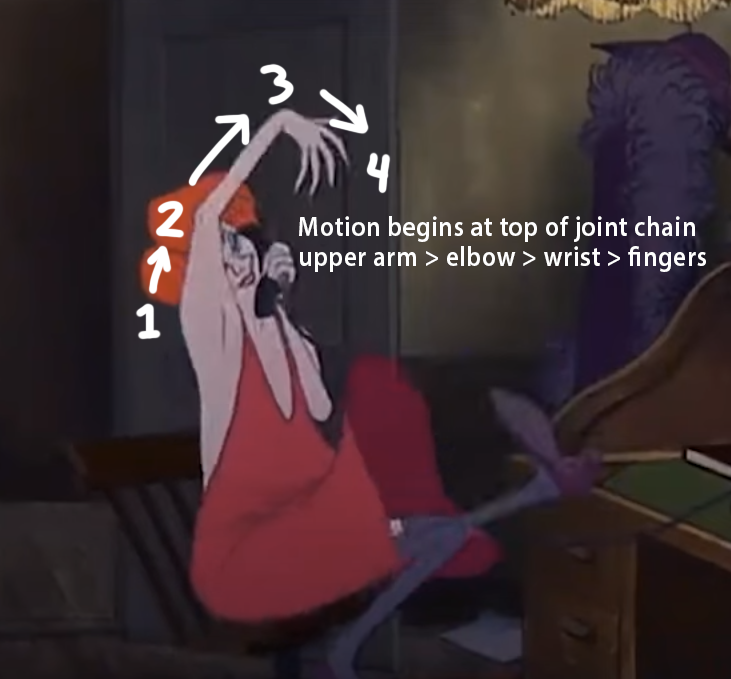

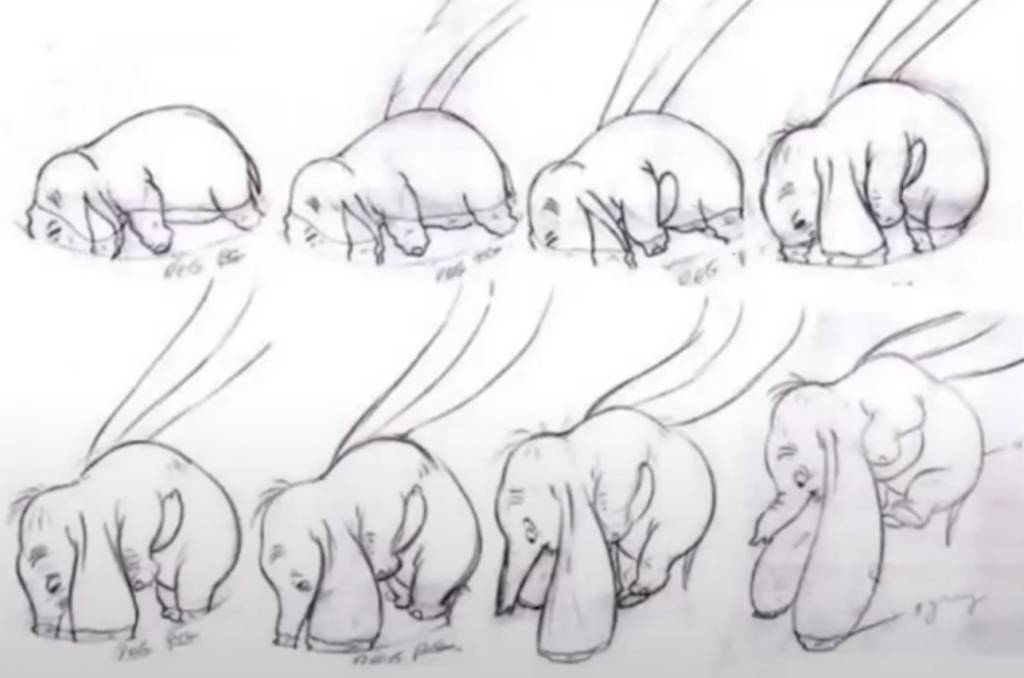

- Tries to simulate the work of a 2D artist

- Rigging needs to give animators the ability to change the model/give the same type of control that they would have if they were to draw the character on paper

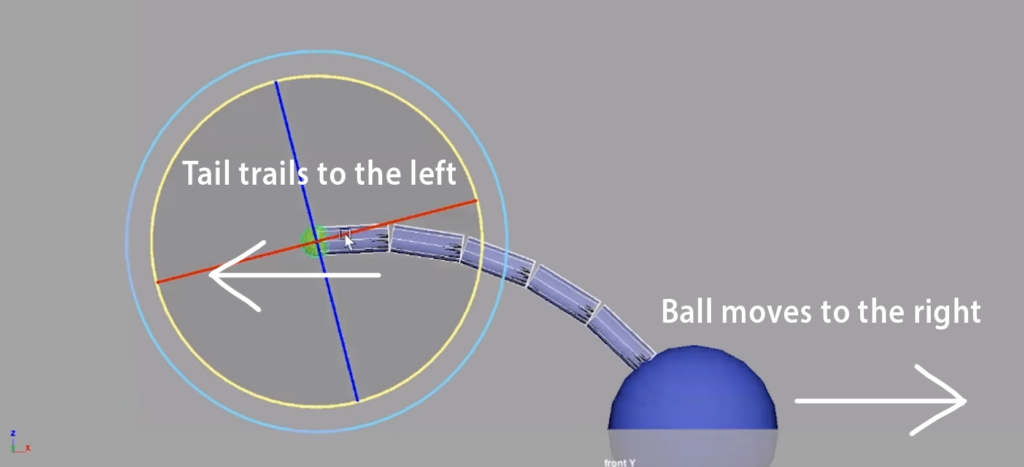

- Oftentimes that means pushing the model with features like squash and stretch

- Give animators the ability to “cheat” certain poses and movements

Visual Effects

- Unlike feature animation, in VFX riggers want to achieve a realistic representation of how the character moves

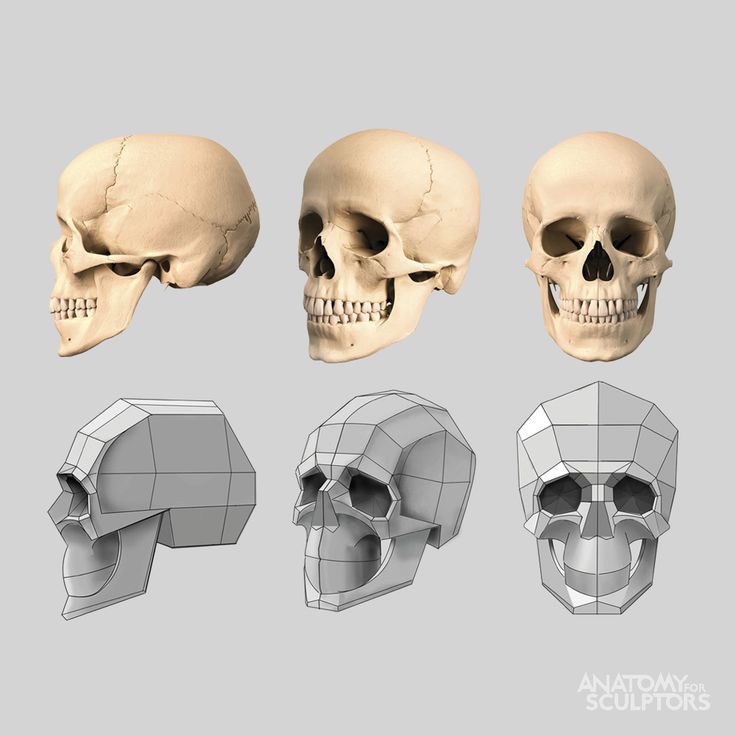

- Important to study the anatomy of the character, even if it is a fictional character; the muscle structure and skin deformation needs to resemble that of the animals we have in the real world

Games

- Keep in mind that the highest concern in video games is performance – riggers must be conservative and cautious of how complex the rig can be

- As hardware improves, rigs can become increasingly complex with less constraints for things like number of joints. However, rendering in real time still carries limitations!

- One of the examples of performance optimization is the level of detail (LOD) that changes depending on how far the character is from the player

- Characters cannot be rendered at the highest resolution all the time, so the model/rig/animation is going to be switched when the player moves closer or farther from an NPC

Other Mediums

- Animations can be exported from 3D applications to a variety of mediums

- For stop motion: models are created in Maya, 3D printed, and then replaced on a physical and tangible model

- Some challenges include the intersection of parts and the thickness of the mesh

- For robotics: animation is created in maya and then exported as code for the physical robot to perform

Analyzing Existing Rigs

It can be extremely useful to closely examine rigs built by other people or companies. It can help in finding features that both work and do not work, see how intuitive the rig is, and look into how it’s built. Try to open up rigs to see how they work; pose them to get an idea of how an animator might use the rig.

Watch the full clip from an AnimSchool lecture here:

At AnimSchool, we teach students who want to make 3D characters move and act. Our instructors are professionals at film and game animation studios like Dreamworks, Pixar, Sony Pictures, Blizzard & Disney. Get LIVE feedback on your Animation from the pros.

Learn more at https://animschool.edu/