Shooting reference is an essential part of the planning phase when animating a shot. It gives the animator an opportunity to step into the character’s shoes and fully explore their personality through movements and acting. Studying reference is a key part of how students learn body mechanics because it allows them to experience the movement and timing of a scene firsthand. Over time though, it is easy for animators to fall into the habit of relying on their reference too much. So much that they begin rotoscoping the reference into their shot, frame for frame.

It is easy for student animators to fall into the habit

of relying on their reference too much.

So does this mean that you should stop filming reference? Of course not! You still need to do reference in order to try out different acting ideas and provide some kind of foundation for the timing and body mechanics of your shot. The key is knowing when you can steal directly from your reference, and when you can simply ignore your reference. Your reference is a foundation, it is—as the name implies—simply a reference. It is an inspiration, something to refer back to, but it is not meant to become a carbon copy of your animation. When animators begin rotoscoping their reference, they forget to think about pushing appealing poses, creating stylized breakdowns, maintain smooth arcs, and deciding what’s leading and what’s following. It’s these decisions that really make animation an art form and the animator, an artist.

Below we’ve compiled a few ways you can avoid falling into the habit of rotoscoping and push your animation beyond your reference to make a performance that’s all your own.

1. Stop putting reference into your viewport.

This is a debatable topic, so it is definitely not for everyone, but we encourage you to try it out. The idea is, that if you put the reference directly into your Maya viewport, there is a greater temptation to copy the poses and the timing of the reference frame for frame. Without the reference sitting in the viewport though, you’re more likely to push the poses and timing of the shot.

Don’t stop using your reference though! If your reference is open in another program such as QuickTime or SyncSketch, you can easily frame by frame through it and pick out the poses you want to use. You can even count the frames in between the poses if you want to get the timing in Maya the same as your reference. But isn’t this just rotoscoping, why not put the reference in Maya and save time? By having your reference in a separate window, you will automatically feel less tied to the reference’s poses and exact timing. Instead of animating on autopilot, you’ll become more conscious of how many frames it takes to get from Pose A to Pose B, and therefore more likely to make the timing more your own.

|

| AnimSchool Student NyGyra Lawson |

Nonetheless, if you’re still adamant about sticking your reference in the viewport, that’s okay! Many professional animators actually prefer it this way. The key point is to remember that animation is an art and as an artist, you need to make decisions about timing, poses, breakdowns, and all the animation principles, independent of your reference. If you copy the timing of your reference exactly frame for frame to start off, that’s fine! Just be sure to go back, and move those keyframes around to really push the timing before you start polishing. You should also keep in mind that sometime during the late spline phase, it’s ok to just turn off your reference. There will be a point when you’ve got everything you could from it, and now it’s up to you as an animator to make the animation really shine.

2. Study the reference in your sketchbook and do a 2D drawing pass of your reference before you even touch the rig.

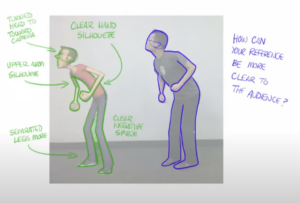

If you like drawing then this tip may be great for you. First, observe your reference and try to get a good understanding of the motion—what’s leading, what’s following, where’s the arc, etc. Once you feel like you understand the reference, pick out your golden poses and some key breakdowns and draw them in your sketchbook or directly on top of your reference (you can do this pretty easily in SyncSketch).

Now that you have a solid understanding of the reference, draw some variations and try to improve the appeal of your sketches. Try pushing some poses or pulling back on others. You can push the timing of certain movements for exaggeration by changing up the spacing. Experiment with spine reversals, line of actions, and even mouth and eye shapes.

By doing this, you’re figuring out a lot of the body mechanics and posing before you even get into Maya. Figuring this stuff out on paper is much faster than in Maya, and you do NOT need to be a good artist to use this method. Trying a new pose out in Maya can take 30 minutes to an hour, but you can easily sketch out a stick figure in a few different variations of a pose in a couple minutes. Working in 2D will also help you avoid getting too caught up in the complex 3D rig, and instead focus on appealing graphic shapes and silhouettes for poses.

They say animation is ultimately 50% planning and 50% animating. Though this planning phase can seem time-consuming, it’ll more than likely be worth it and make your animation not only better but quicker to complete.

Here is an example of some planning thumbnails from AnimShool’s Body Acting Class.

|

| AnimSchool Student Rhys McKenzie |

3. Push the poses in Maya.

This is probably the most obvious way to go beyond your reference: push the poses!

The biggest things to remember when translating a pose from reference to the rig are line of action, silhouette, and character. Oftentimes, humans aren’t the most elegant creatures and our line of actions can feel a bit disjointed no matter how much we try. This is where you as an animator can come in and make the poses your own. Try and simplify that line of action, in one coherent statement that supports the way the character is feeling. Doing this will not only improve the clarity and appeal of your pose, but it’ll also allow the character’s thoughts and feelings to read better. Improving the silhouette of your character can have a similar effect as well. Ensuring that limbs and hands don’t get lost in a character’s body will allow your character’s emotions to be read with clarity. They say that after the eyes, hands are the most expressive part of a human, but if you can’t see the hands because they’re lost in the character’s silhouette, the pose ultimately doesn’t read as clearly as it could.

AnimSchool instructor Garrett Shikuma does a fantastic job of demonstrating some methods to push a character’s pose to be better than the reference. Though Garrett says you can always push your poses, he emphasizes the importance of remembering to make intentional acting decisions while posing your character as well.

We hope you found some of the methods useful. What are some of your best tips for animating with reference?

Join our online community of 3D artists and animators in our online accredited courses (ACCSC). Apply today at animschool.edu